The Decline of the Antoninianus

Resources

- Antoninianus

- Nature: FIB-FESEM and EMPA results on Antoninianus silver coins for manufacturing and corrosion processes

Introduction

The antoniniani (singular: antoninianus), also referred to as “pre-reform radiate” and “double denarius”, was a denomination during the Roman Empire, although its ancient name is not known to modern scholars. This denomination tells a tale of the Roman Empire during a period of crisis and unceasing transformation, and is an important part of Roman monetary history.

The creation of the antoninianus

The antoninianus was introduced by Emperor Caracalla (nicknamed after Gallic hooded tunic he wore) in 215 AD, due to his problematic financial situation. During this time, the Roman Empire paid for its expenses by gold and silver from mines and successful wars. When these options were limited there were two straightforward options: not to pay or to debase the currency. Caracalla promised the Roman army payment, but the existing silver inventory was not sufficient to mint enough denarii. He introduced the new denomination to solve the problem. The antoninianus gradually replaced the denarius, which was minted until the reign of Gordian III, and afterwards only in very small quantities likely for ceremonial purposes.

The name “antoninianus” comes from Caracalla’s real name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. Initially, the coin was in silver but later on heavily debased by mixing in bronze. The antoninianus was first valued at 2 denarius, although it’s initial silver content only was worth 1.5 denarius.

Seigniorage is the difference between the value of money and the cost of producing it (price spread), essentially it’s the profit that a government earns by producing currency and can be seen as a form of inflation tax. The word comes from old French seigneuriage, “right of the lord (seigneur) to mint money”. The seigniorage of the antoninianus created inflation as shopkeepers had to raise their prices to match the debased new currency. Allegedly, people started to collect the denarius (the older silver denomination) and pay with the antoninianus. This is consistent with Gresham’s law that states that “bad money drives out good money”. If two types of commodity money circulate and are legally recognized as having equivalent face value (nominal value), the commodity with the higher intrinsic value (the value of the precious metal, e.g., silver) will gradually be withdrawn from circulation.

At this point in time, the Roman Empire did not expand and its current silver mines where running short, therefore the antoninianus was minted with less and less silver over time, leading to an increasing inflation. In the late third century the antoninianus was almost fully debased to bronze. This lead to a hyperinflation not unlike the Weimar Republic in 1920s Germany.

Silver content of the antoninianus

Even in the beginning, antoniniani coins were not made of pure silver. Initially, the antoninianus was minted with approximately 50% silver. However, in the late 3rd century the silver content of the coins were merely 5%. The bronze used for these coins, in the late 3rd century, could come from melting down older issues of bronze sestertius (another Roman denomination).

During the time, the antoniniani were produced it was common with a “depletion silvering” technique. In this process, coins were made from a base metal core (usually bronze or copper) and were then treated to give them a surface layer of silver. Here’s a simplified explanation of how depletion silvering could work:

- Creation of the Alloy: The base metal, typically copper, would be alloyed with silver.

- Striking the Coin: The alloyed metal would be struck to form the coin.

- Acid Bath: The struck coins would be placed in a corrosive acid bath. The acid would remove metals from the surface but would be less effective at removing silver than the base metal.

- Washing and Polishing: After the acid treatment, the coins would be washed to remove the remaining acid and then polished to give them a shiny appearance.

- Final Product: The end result would be a coin with a higher concentration of silver on its surface than in its core, giving it the appearance of being made entirely from silver.

This method was less expensive than using pure silver but gave the coins a similarly valuable appearance, at least when new. Over time, however, the surface silver layer could wear away, revealing the less valuable base metal underneath. The depletion silvering technique is an interesting example of ancient metallurgy, revealing the kinds of compromises and innovations that civilizations have made in the face of economic challenges.

The mint workers uprising and the Aurelian reform

Aurelian was a Roman emporor who reigned 270-275 CE, right in the middle of the crisis of the third century. Aurelian was not of noble birth, but climbed the ranks of the military and eventually led the cavalry units under emperor Gallienus. During this time mint workers had started to debase the antoninianus further by stealing silver from the mints (Watson, 1999). Aurelian wanted to stop this defraud of the government and as a response the mint workers rebelled. The revolt eventually ended after harsh measured and Aurelian introduced a monetary reform afterwards.

Aurelian introduced a “new” antoninianus with 5% silver, which was above the current standards. These new coins had the mark “XXI”, meaning that they contained 20 to 1 ratio of bronze to silver, i.e., 5%. The “XXI” mark can be seen on later anotoninianii as well, e.g., see the reverse of the Diocliatian antoninianus in this article.

Barbarous radiate

Postumus Usurper antoniniani

The crisis of the 3rd century in the Roman Empire was a period spanning 235 to 284 CE. Amid an economic downturn, the empire faced domestic political turmoil, military upheavals, and constant external invasions. By 268 CE, Rome was divided into three distinct states: the Gallic Empire in the west, the Palmyrene Empire in the east, and the core Roman Empire. This period saw the rise of at least 26 contenders for the emperorship, a chaotic situation that persisted until Diocletian restored central authority in 284 CE.

One of these contenders was Postumus, who was a Roman commander of Batavian origin. Batavi was an ancient Germanic military tribe controlled by the Romans, around modern Dutch and the Rhine river delta. Batavi had a fairly long history with Rome. For example, the Numerus Batavorum or the “Germanic Bodyguard”, was a guardian unit for Roman emperors from Augustus to Galba. Another example it the “Revolt of the Batavi” refers to an even that took place between 69-70 CE, where the Batavi military went to war against the local Roman control. The Batavi successfully delivered multiple devastating losses to the Roman military forces, notably annihilating two legions. Following these victories, a Roman force under the command of General Quintus Petillius Cerialis ultimately subdued the Batavi forces. Subsequent negotiations led to the Batavi’s reintegration under Roman dominion, albeit under demeaning conditions and the imposition of a permanent legion within their lands.

Postumus reigned as emperor over a break-out state of the Roman Empire referred to as the Gallic Empire. The Roman emperor Gallienus ruled 253-268 CE, and stuck down many usurpers and rebels during his time, but failed to stop Postumus who rose through the ranks of the army and took command over the provinces in Gaul, Germania, Britannia, and Hispania. By 261, Postumus was recognized as the emperor over these regions. He established his base at Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium which was a Roman cology, at the modern city of Cologne, and made it the capital of the Gallic Empire.

Gallienus led several campaigns to defeat Postumus without success. Postumus was successful in his task to initially stabilize the Gallic Empire. However, the economy became strained and his Spanish silver mines ran dry, leading to a debasement of his antoniniani. Postumus had competition from others wanting to claim the thrown and eventually he got killed by his own soldiers in 269.

Nevertheless, during Postumus prosperous year his antoniniani minted at a higher silver content than the contemporaneous coins of Gallienus. Postumus minted a series of gold coins called “Labours of Hercules”, his favorite deity. Because of the high silver content and fine gold coins, the Postumus coinage have been of specific interest to modern day numismatists.

Below is an antoninianus of Postumus, minted in Cologne, Lower Germany, between 263-265 CE, with RIC V Postumus 323. The obverse shows a bust of Postumus with a radiate crown with the legend “IMP C POSTVMVS P F AVG”. The reverse, shows the diety Providentia holding a scepter and a globe, with the legend “PROVIDENTIA AVG”.

Diocletian’s monetary reform and the end of the antoninianus

The antoninianus stopped being produced around the time of Emperor Diocletian’s currency reforms which began in 294 AD. Diocletian introduced a variety of new coins, most notably the follis, also known as the nummus. These reforms were part of his broader efforts to stabilize the Roman Empire, which at the time was suffering from inflation, civil wars, and external threats. Diocletian tried to introduced maximum prices that merchants had to obey, however this was not enforceable and prices continued to rise.

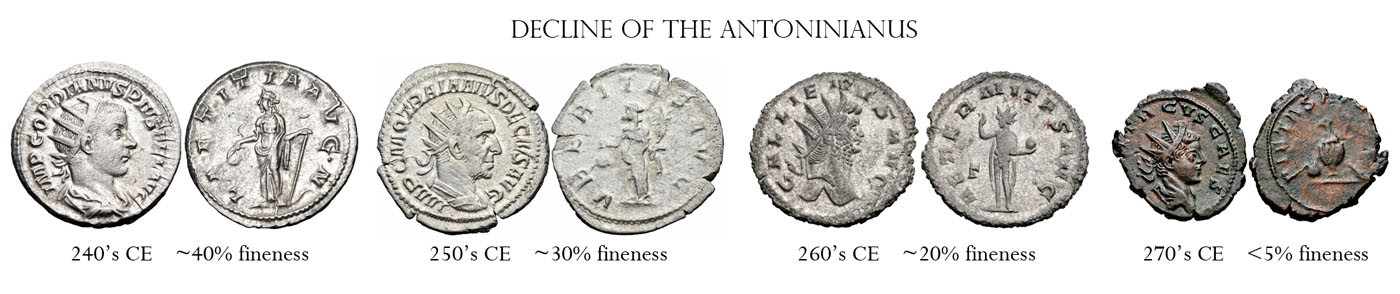

A set of antoninianus over time

Below is a picture from my collection showing the decline of the antoninianus over time,

The radiate crown, is a type of crown that has spikes or rays emanating from it, often used to symbolize divinity or a connection to the sun god, Sol. On the coins, the radiate crown indicates that the denomination is the antoninianus.

Attribution of the coins in the picture

Coins in the Roman Empire were a source for propaganda and they tell interesting stories. Today these stories both consist of the mythical Roman stories, but also the tide of history they tell.

1st coin: Antoninianus Caracalla (198-217 AD)

Resources:

Attribution:

- Issuing state: Rome

- Authority: Caracalla

- Denomination: Antoninianus

- Date: Struck 215 AD

- Mint location: Rome mint

- Observe: Radiate, draped, and cuirassed bust right

- Observe legend: ANTONINVS PIVS AVG GERM

- Reverse: Jupiter standing right, holding thunderbolt and scepter

- Reverse legend: P M TR P XVIIII COS IIII P P

- Diateter (mm): 23

- Weight (g): 4.45

- RIC number (Roman Imperial Coinage): 258a

This coin is very interesting as it is an antoninianus from the first year the denomination was minted. Caracalla introduced the denomination in 215 AD and this is one of the examplars from that year.

2nd coin: Antoninianus Philip the Arba (244-249 AD)

Resources for the coin:

Attribution:

- Issuing state:

- Authority: Philip the Arab (Imperator Caesar Marcus Julius Philippus Augustus)

- Denomination: Antoninianus

- Date: Struck 244-249 AD

- Mint location:

- Observe:

- Observe legend: IMP M IVL PHILIPPVS AVG

- Reverse:

- Reverse legend: ROMAE AETERNAE

- Diateter (mm):

- Weight (g):

- RIC number (Roman Imperial Coinage):

I recently acquired my first ancient roman coin, which is an Antoninianus from around 244-247 AD. The obverse of the coin depicts a bust of Philip the Arab with

The observe legend “IMP M IVL PHILIPPVS AVG” translates to “Emperor Marcus Julius Philippus Augustus”. Where “IMP” stands for “Imperator”, and the rest is his name, “M” for “Marcvs”, “IVL” for Ivlivs (Julius), and “AVG” for “Avgvstvs”. Augustus was a Roman title that means “venerable” or “consecrated”. It was adopted by the first Roman Emperor, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (often referred to simply as Augustus), who reigned 27 BC - 14 AD. Thereafter, Roman emperors added the title to their regnal names.

The reverse legend “ROMAE AETERNAE” translates to “Eternal Rome” in English. This phrase often appears on Roman coins and other inscriptions to pay tribute to the everlasting nature of the city and the empire. It reflects the Roman belief in the perpetual endurance and grandeur of Rome, a sentiment that was widely propagated during various periods of the Roman Empire.

On the reverse of the coin you can see Roma seated with a shield. She is holding Victory in her right hand and a long scepter with her left. In ancient Roman religion, Roma was the personification of the city of Rome and the Roman state. In Roman artwork and on coins, she is often portrayed in a military guise, with a helmet and carrying weapons. Her portrayal, seated with a shield and spear, later inspired the image of Britannia, the personification of Britain. The small figure of Victory, often depicted with wings, symbolizes a military triumph. The scepter is a traditional symbol of authority and governance, emphasizing the lawful and just rule of the emperor and the state.

Identifying the coin can the done on the American Numismatic Society’s website. I searched for the observe and reverse legends (IMPPHILIPPVSAVG and ROMAEAETERNAE) and that yielded 7 possible results.

Ancient coins can have many variations, even within the same emperor’s reign or from the same mint. Minor differences in design, inscriptions, or wear can create challenges in identification, so having access to specialized resources or professional guidance may prove invaluable in determining exactly which coin you have. Roman coins were struck by hand, and I have heard that the reverse die could wear out quicker than the observe die, meaning that the same observe die could be used with several different reverse dies.

Attribution: Resources:

4th coin: Antoninianus Carinus (282-283 AD)

Attribution:

- Issuing state: Rome

- Authority: Carus

- Denomination: Antoninianus

- Date: Struck 282-283 AD

- Mint location: Rome mint

- Observe: Bust of Carinus, radiate, draped, cuirassed, right

- Observe legend: M AVR CARINVS NOB CAES

- Reverse: Carinus standing left in military attire, holding sceptre and signum; KAЄ in exergue (mint mark)

- Reverse legend: PRINCIPI IVVENTVT

- Diateter (mm): 23

- Weight (g): 4.42

- RIC number (Roman Imperial Coinage): 158

The portrait on the observe on this coin is Carinus who was the son and co-emperor of Carus. Carus was emperor 282-283 AD and when he died he was succeeded by his sons Carinus and Numerian.

References

- Watson, Alaric (1999), Aurelian and the Third Century, Routledge, London.